A car drove into my business and now everyone loves us for a minute.

Is talking about tragedy on Instagram really what it takes to "drive" sales?

I woke up at 1:30 Sunday morning, confused that my phone was making a sound that wasn’t my ringtone, Slack, or WhatsApp. I picked it up and saw several missed alerts from the alarm company. I swiped open the app to view the live camera in our retail space and saw shelving knocked over, plants and loose dirt, and broken pottery. Most terrifying, I heard voices. I couldn’t see people, but I could hear them off camera.

This is my nightmare, waking from sleep and having to deal with the bewildering reality that people are smashing up the business with baseball bats.

The alarm company called. Do I want police dispatched? Yes, I told them. Something’s going on in there, I can’t tell what.

This isn’t the first time the alarm has gone off in the middle of the night—bullets coming through the windows, things falling and setting off the motion sensor—but this is the first time I’ve seen something terrifying on the live cam, the first time I felt the need to go to the scene. I woke my partner and started pulling on clothes.

As I was getting ready, police called. Officers were already on scene, they said, because a car had crashed into the front of the building.

Do you know what I felt at that moment?

I felt relief.

Oh, good. A car crashed into the front of the building. This was a random accident, not a targeted act of violence.

Also, I knew this would happen.

From the moment we signed the lease on our South Tacoma shop in July of 2020, I had a feeling that some day a car would smash into the front of it. Our four-block stretch of boulevard is a business district, with buildings set closer to the street and a landscaped median, but to the north and south of us, South Tacoma Way is a four-lane throughway where people love to drag race. Our storefront isn’t shielded by the median, we’re right on the intersection. It’s just a matter of time, I thought, until one of these vehicles driving 60 mph through a 25-mile zone loses control and smashes through our wall.

It happened to Native Poppy, a flower shop in San Diego, about a year ago. It also happened when I was in high school. A driver had a seizure and lost control of their vehicle, smashing through the front wall of our cafeteria. So, you know, it’s something I know can happen.

And on Saturday night, it happened at Fernseed.

The driver was arrested and charged with reckless driving. Surprisingly, no one was injured in the accident, though it happened at 12:30 a.m. when people are still bar hopping.

The fire department boarded up the windows and deemed that the damage was not structural. I got a few hours of sleep, then made a list of things to do that morning: notify my team, message the building owner, get a copy of the police report, call our insurance company, and—oh, yeah—post about the accident to Instagram.

We were going to be closed for a number of days, so it felt necessary to post an update. For better or worse, Instagram is the best channel for this type of communication, and yet, I hate drawing attention to the business in moments like this.

It’s not the “negative publicity.”

It’s the complicated relationship I have with the need to publicly address a crisis that has an impact on our business, but that I do not want to make myself the center of. This started with the pandemic.

In March of 2020 I did a series of Instagram posts explaining how the shop was handling closure and how customers could order from us. Before PPP money, before unemployment insurance bonuses, before we even knew if we needed to sanitize our groceries, there were a lot of unknowns, so I feared that a pandemic shut-down would force us out of business. But the pandemic was also killing people. On the scale of things, does it matter that a plant shop closes? It felt weird to ask people to help us stay in business, but it also didn’t feel right to go dark on social media if we had a chance of survival by selling online.

I thought that, rather than centering our business or just talking about plants, I could demonstrate to other business owners how we get through this. I could be helpful! I felt more at ease talking about the meta side of the business on Instagram, but this type of content wasn’t helping sales when we desperately needed them, and mostly what our Instagram audience wanted to talk about was plants.

So we gave them plant content. They ordered plants online, and my team took shifts packing them up, delivering and shipping them, and creating Instagram content about how to take care of plants. Hundreds of thousands of people dying! But people on Instagram wanted to know, “Why is this leaf turning yellow?”

Something about that disconnect fucked me up. To this day I get anxious talking to people about plant care, though I would like to get back to a place where it feels like a joy. It’s hard when there’s always a crisis.

When a car crashes through the front of your shop, you suddenly become very afraid (again) that the temporary closure will put a dent in your sales that is unsurvivable. Cash flow is a real concern around here.

Are we covered by business interruption insurance? Yes, after a 72-hour waiting period. Will the damaged merchandise and furnishings be covered? Yes, after our $1,000 deductible. But those claims take a while, and I need cash by the 7th or the two checks I just floated to our largest vendor will bounce. I need $4,500 no later than the 5th for rent. By the 12th I’m going to need that amount again for payroll.

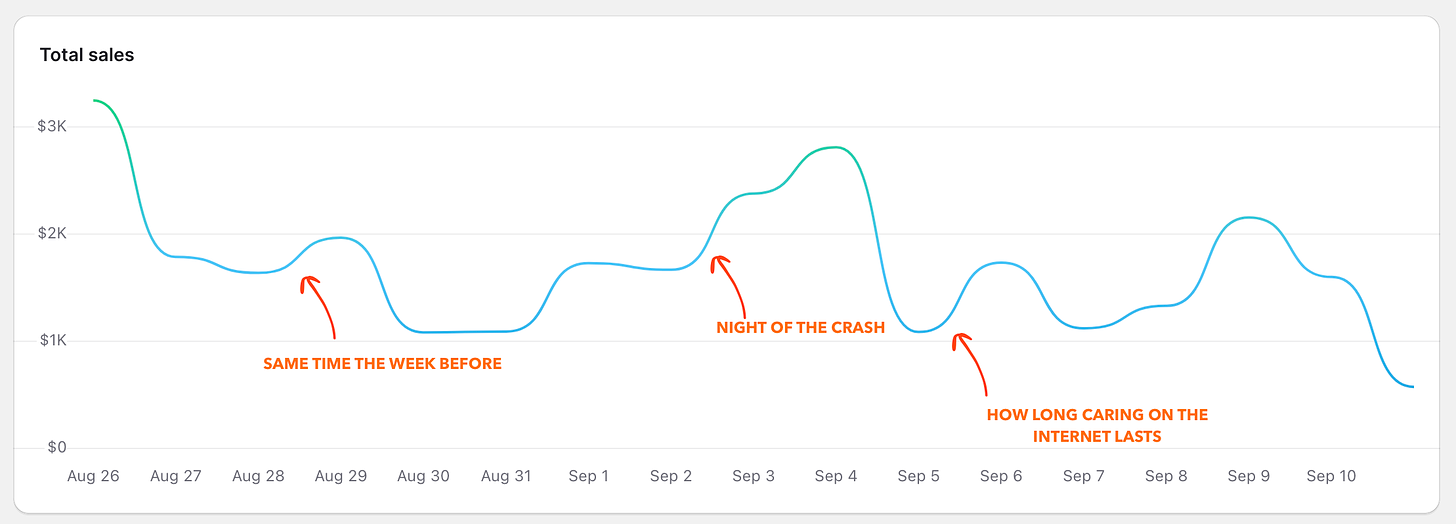

It feels ridiculous to me—although not unexpected—that this accident prompted people to spend more money than they typically would at our shop last week.

I knew, for better or worse, that you really can’t create more effective social media content than what is provided to you for free via your security camera footage when a destructive incident occurs in your storefront. If you want proof:

Want to see the video of the car crashing into my shop?

I knew the crash post would get stratospheric engagement. Instagram values tragedy, polarization, and content that encourages parasocial relationship building. If I want to post successful content on Instagram that eases our cash flow crisis, then I need to feed the algorithm with every bad thing that happens to us, post controversial content, and share personal stuff that makes customers feel like they know me when they don’t.

I read an article about East Fork Pottery in the New York Times last year that alluded to this phenomenon and how it impacts small businesses.

But the ceramics are not the only reason customers are drawn to East Fork, Ms. Javeri Kadri said. “People often get excited by the story, and by Connie and how magnetic she is,” she said.

Since the company’s inception Ms. Matisse, who for the past two years has served as its chief executive, has played an integral role in how it communicates with the world.

She has written or signed off on blog posts that note exactly how the Mug is made and explain why, in a state with a minimum wage of $7.25, East Fork’s salaries now start at $22 an hour. She has written email newsletters, including one about how to clean dishes, in which she also grappled with her work-life balance (she has two young children). She has posted selfies taken in her bathtub to East Fork’s Instagram account. Some, like a post advertising job openings, relate to the business. Others, like a post calling out body shamers, do not.

The post goes on to describe how Connie Matisse, the CEO and brand voice of East Fork, had to grapple with the mental toll of radical transparency on Instagram when just keeping the business from collapsing was stress enough. And here’s the double bind: each time she’s tried to let others in the company steer the marketing voice, Instagram engagement has plummeted. In other words, if she doesn’t feed the machine photos of herself in the bathtub with argument-provoking captions, people stop buying dinner plates. If you were Connie Matisse, wouldn’t you think twice about making this the month you refuse to keep using your story as marketing content, knowing that if you just posted about your marital struggles, how the demands of the business are preventing you from spending quality time with your kids, you’d probably hit those Q4 revenue goals and you wouldn’t have to lay anyone off?

But you also know each time you squeeze a drop of blood for the insatiable social machine, you’ll get a half dozen comments telling you to stop whining, or worse. Maybe they’ll Google your address and share how much your home is worth, just to prove that you could always mortgage your house to save the business instead of waxing about failure and morals on Instagram.

I was just reading this Substack piece by Tara McMullin that read, in part:

… it's important to note that businesses don't benefit from "improvements" in the economy in the same way [corporations do]. I've previously argued that small business owners and independent workers have more in common with workers than they do with corporations.

So, while large corporations are doing just fine (even seeing record profits), it follows that the small business owners and independent workers… are feeling the squeeze.

… most [small business owners and independent workers] don’t have access to a public safety net as traditional workers do. Nor do we have reserve cash to tap into or massive expense budgets we can tighten as corporations do.

I appreciate this so much because it makes concrete something I feel so deeply but can’t quite articulate: that as a small business owner in a mid-size city, I’m not any more empowered to do anything about the systemic issues than traditional workers are, and in fact I have even less of a safety net than some traditional workers.

I’m also caught in the double bind of needing money now, and recognizing that sometimes the easiest and quickest way to get cash is to cry for help on social media. It’s like the payday loan of the internet. The only drawback is the risk of public character assassination.

To be clear, I’m open to criticism when it’s coming from a good faith source, when it’s real dialog aimed at reaching understanding and equity for all. As small business owners operating in a system of racial and economic inequity, I believe we have a greater obligation than “traditional workers” to examine our inherent biases and privilege, because our misuse of either can result in greater damage given our influence. But we all need to be mindful of the difference between influence and power. Having lots of social media followers means that sometimes when I post things to the business account, a lot of people see it (mostly if I use a personal, confessional approach). That doesn’t mean I can enact real, systemic change.

This issue primarily impacts women in business, who may have started sharing about the growth of their companies with a few hundred followers in the early days of Instagram because that was the path to success we saw modeled when traditional paths, like securing investment, failed us specifically. The only way we could bootstrap was to use our personal narrative as collateral: our fears, our failures, our relationships, our tragedies, our children. Then one day we find ourselves in the position of running actual companies, work that is hard enough without adding the toxic stress of backlash from vulnerability that is now shared with an audience of people you don’t know. It’s unsustainable and for some business owners, it’s inescapable, because the second you take your foot off the confessional throttle, your sales are impacted.

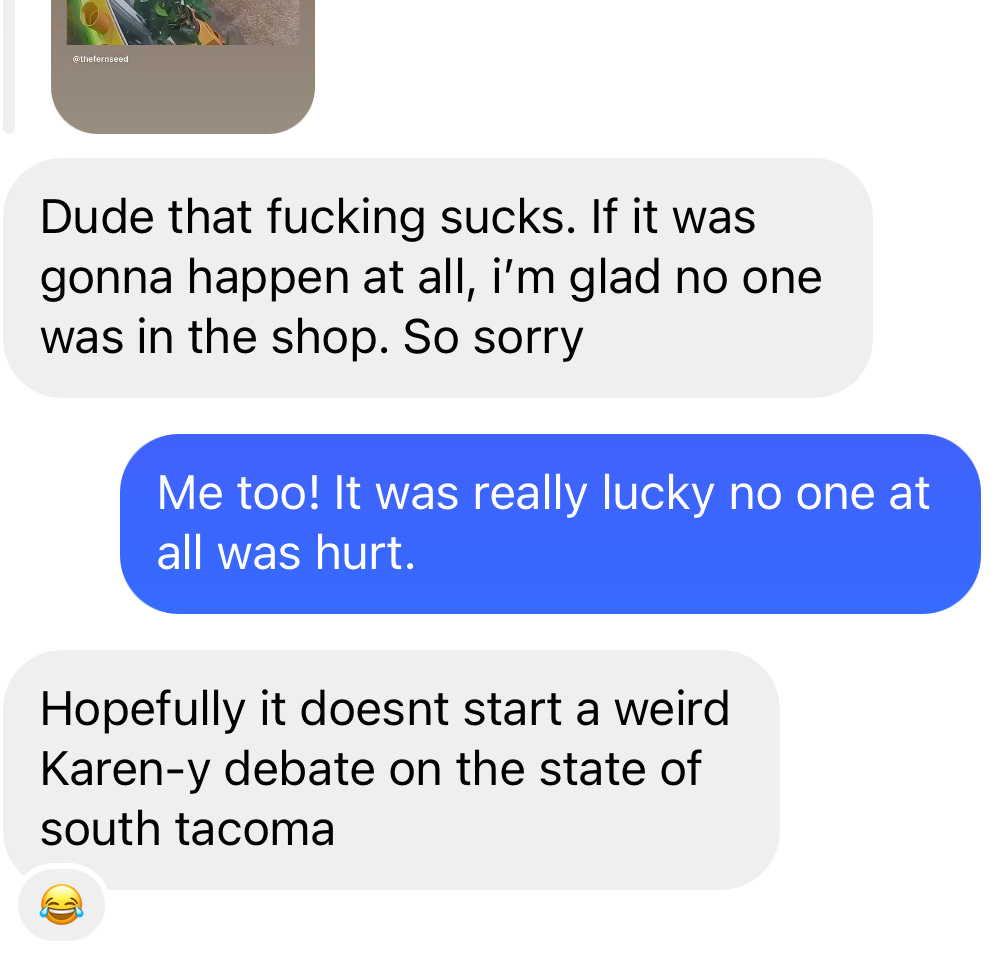

My friend, who happens to manage a small business, sent me this DM after she saw the post about the accident:

It’s comforting to be seen. She knew the real issue wasn’t cleaning blood and glass off the floor, but the potential that a grid post about the accident could turn into an attack on me, or my team, or some aspect of my business, or the tone of my post that I didn’t thoroughly think through in the 12 minutes I had to post it.

Is that a stretch? Not really, because it’s happened before. I wrote previously about a road rage incident across the street from our shop that resulted in someone’s death and the social media outrage—directed toward two young women who worked for me—that followed. What almost got lost in that incident was not only the death of Victor Scott, but the feelings of the two women who worked for Fernseed who had witnessed a fucking murder and were not allowed any grace for how they handled it.

I would argue it was not the two Fernseed employees who used the Citizen app to report police activity who were being insensitive to the gravity of the (still unfolding) situation. It was the Citizen app commenters who steered the conversation during the livestream to a conversation about the fucking plants.

Sift through the comments on the car crash post and you’ll find them there, too.

“Were the plants salvageable? 😢”

“The plants on sale that [got] smashed? Lol”

“Have you thought about selling the damaged plants at a discounted rate?”

And whatever, the plant comments are fine. Really. We’re used to it at this point. We’re a plant shop. People can ask about the plants! Does the dog die? I get it. At least you’re not posting comments about my home value.

But here’s the place where this shit gets rough for me.

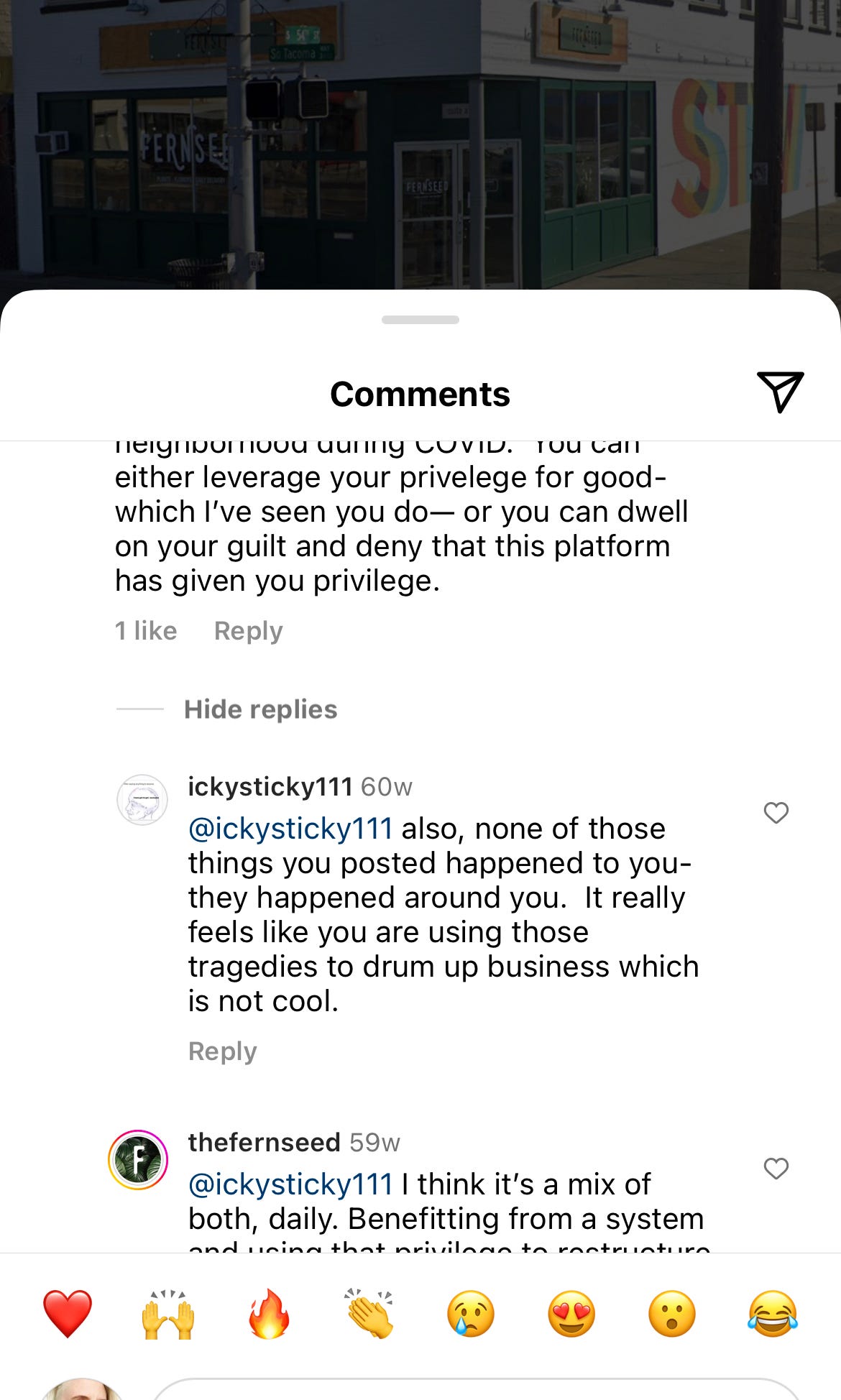

This is a year-old comment on a Fernseed Instagram post about a nightclub shooting that resulted in multiple injuries. It happened at a venue down the street owned by my landlord and friend. The context of the Instagram post (which I wrote the day after) was that it felt like a weird day to post about “plant business as usual” when this tragedy had happened, that we love this neighborhood, and that we want to be a place where people can shop and feel safe… but also that Instagram is a heinous tool that requires almost daily updates to ensure sales don’t plummet even when it feels weird and gross to talk about anything.

And that post led to the accusation that I am dwelling on my guilt, and misusing my privilege.

Now of course I was born with certain privileges—being white, cisgendered, heterosexual, from middle class upbringing—and I recognize the power those advantages give me in certain circumstances. I have tried, imperfectly of course, to use whatever power I have to advance the cause of justice and equality in my business and personal life (which this commenter generously acknowledged, thanks). But like all small business owners and humans, there are moments where I’m down for the count. The additional privilege I was able to “leverage” at the time of this post was a home value I could mortgage to keep the business from plummeting into insurmountable high-interest debt, and a partner who had job that paid well enough that I could stop paying myself anything at all.

And look, am I defending myself in a Substack post against a year-old Instagram comment because I took it personally and felt attacked?

FUCK YES I AM. But like my early-pandemic business posts, I’m doing it for a greater purpose: to say that if you are also a small business owner, if a comment like this hasn’t already happened to you, I can pretty much guarantee you that it will. And when it does, please remember the East Fork double bind, and what Tara McMullan wrote about small business owners being perhaps less resourced than some traditional workers. We are damned if we do, and if we don’t, we might go out of business. Not everyone recognizes that, especially not on Instagram.

I can also pretty much guarantee you that a car might drive into your storefront at some point. It happens more often than you think.

I was recently invited to a roundtable discussion at a Tacoma city council meeting where another Tacoma business owner said this:

Tacoma loves a first and a funeral. There are always lines when you open, and when you announce that you’re closing, everyone shows up to shop the sale and ask what happened. We need more help in the middle.

I wish it didn’t take a tragedy, or a shop closure, to get the community to rally around any business.

I wish the community recognized that it wasn’t the car crashing through the wall that put us at risk, that the shops in their neighborhoods are always vulnerable to forces outside of our control, and to commit to spend money locally, not just following a tragedy, but all year round.

I wish business owners didn’t feel the pressure to talk about the struggles—personal, financial, professional, or otherwise—to generate reven

ue.

Then we could get back to just talking about the fucking plants on Instagram. 🌵🌱🪴

I relate very much to this. It's a heavy and strange aspect of being a small business owner in 2023 that not enough people talk about -- thanks for writing about it here!