You need to raise your prices [part two]

How anchor pricing and ignoring behavioral science holds you back, and the simple math to break free

This is the second post in my series about raising your prices. If you haven’t already, check out my first post, which explains why I think raising prices is the smartest (and maybe only) path to increased revenue for storefront retail businesses.

In this post, I’ll talk about how we leave money on the table by pricing items based on “anchor” (a.k.a. wholesale) prices set by our suppliers, the human behavioral science behind perceived value, and finally, the simple math that demonstrates the dramatic impact price increases may have on your small business.

“What someone will pay for it” = what something is worth

I had a really bizarre job in my twenties working for an estate liquidator who bought auctioned off public storage units, then paid people to haul whatever potentially valuable stuff was in them back to their Chicago walk-up apartments, research the items, then list them on eBay. The rule was auctions had to start at $0.99, $4.99 or $9.99, depending on what our cursory research told us each item might fetch in a 7-day auction.

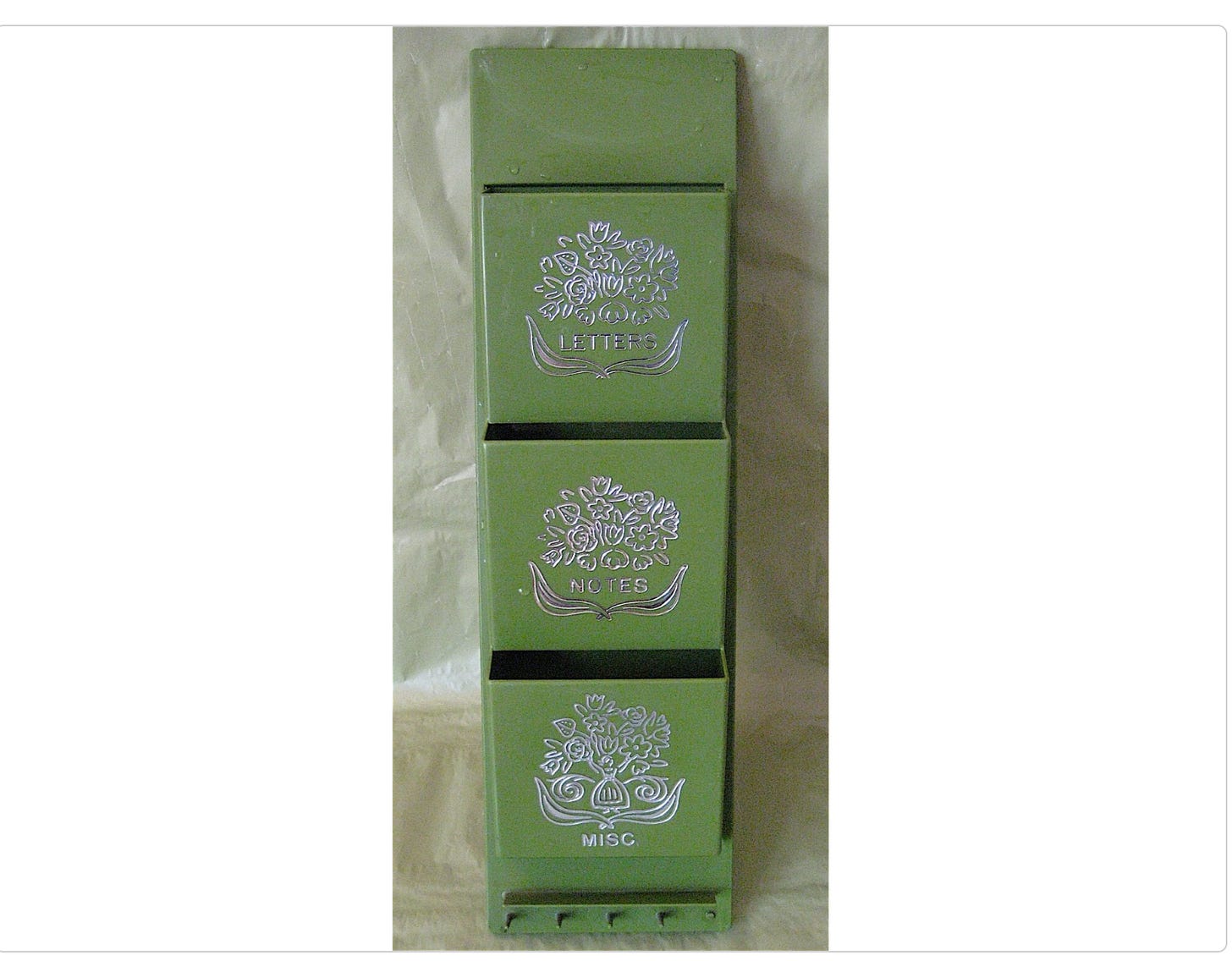

I learned so much doing this job, like the difference between pressed and blown glass, what a Lladro was, and how to spell "memorabilia." But the most important lesson I gleaned from listing hundreds of things at online auction was that stuff I thought was coo, like an avocado green 1970s mail organizer or a macrame owl wall hanging, wouldn't even sell on eBay for 99 cents.

Rich, my storage auction boss, said it was okay for me to keep some of these things because they'd just get donated to the thrift store anyway, so I started a little collection of kitsch decor that I was sure someone, someday, would buy from me.

Then somewhere around 2007 or 2008, Etsy, the handmade marketplace, launched a vintage category. This was my moment! I immediately started an Etsy shop, and when I listed the avocado mail organizer for $12, it sold within a week.

Why did it sell on Etsy for $12 when it wouldn’t sell on eBay for a dollar?

Because to shoppers, Etsy means something different than eBay. It’s curated! It has an “it” factor. (Well, it did back in 2008.) On Etsy, the sellers themselves were cool!

It was the cachet Etsy lended the object, and not the object itself, that held the value. Later as I got better at curating and photographing for my Etsy store, I found I could sell things that actually had no value—like found, painted frozen orange juice canisters—because I contextualized them for a new buyer.

When it comes to pricing, context is everything. For example, at a gas station, you might expect to pay $1.99-2.49 for a bottle of Topo Chico sparking water, whereas at a fancy street taco restaurant, you’ll pay $4-5. While five dollars would seem like a ridiculous amount to pay next to a $2.69 bottle of Gatorade, it seems like a more affordable drink option when you contrast it with a $14 margarita.

The product itself doesn’t change, but the context does, and it’s the context that justifies the price increase.

Think people won’t pay $5 for something they can get down the road for half that price? Think again. Pricing experiments have proven time and again that people expect to pay more for things, and will, in different settings. Most of the time, it doesn’t even bother them!

If you worry that your customers will spot the difference and resent you for it, ask yourself: what small improvement can I make to this product or packaging that will justify the higher price point in the consumer’s mind, without adding much to my cost?

Can you add a fancier ribbon? Put it in a box? Make it with slightly nicer paper? How about serving glass bottles of Topo Chico instead of plastic? If you serve it with a glass of ice (free) and a wedge of lime (basically free), don’t you think this Topo Chico is now definitely worth five dollars? Your customers will.

Divorce yourself from price, think about value instead

“Anchoring” is the term for a well-known cognitive bias that refers to the human tendency to give too much weight to the first price offered in a negotiation. The first number, “the anchor,” becomes a subconscious reference point that unduly influences the final price. This is why business coaches encourage entrepreneurs to make the first offer in a negotiation, because they’ll have more control over the final outcome.

We tend not to think about anchoring when we price products for retail, but we should. Product pricing is a negotiation, both with your supplier and your customer. What is the “anchor” in this negotiation? It’s still the first number that’s thrown out: the wholesale cost of the item dictated to you by the supplier.

How many of us price products for retail based almost 100% on that wholesale price? I would wager most of us do, because the wholesale cost is the first point of reference we have in pricing. This isn’t to say you should try to negotiate that price lower. It’s simply to say that we should probably divorce ourselves from that price once we know it.

“Prices are a collective hallucination.” — William Poundstone, Priceless

That wholesale cost now has an undue influence on how we price for our customers, which is the second part of our negotiations. While most of us don’t allow haggling, we don’t always expect customers to pay our tagged retail prices, do we? The stated retail price on a product is really just the beginning of a negotiation with the customer that sometimes includes sales, coupons, and bulk discounts. If you don’t start your offer high, do you really have room to decrease prices to drive sales later?

What if we never saw an opening dollar amount from our suppliers? What if we used our experience as shoppers rather than our experience as buyers to create a pricing strategy? That would mean instead of asking, "how much did we pay for this?" as the beginning of our price strategy, we would ask, "What would one of our customers probably pay for this?"

If Fernseed would have used this strategy from the beginning, we’d be better off today. Let me walk you through my reasoning.

The way we used to price things

If Fernseed were selling bottles of Topo Chico using the same pricing strategy we used to use when we priced plants, we would start with the wholesale price of the bottle: $1.39. Then we would double that price to arrive at a 50% margin ($2.78), then round up: 3 dollars.

That’s more than the gas station charges, and a 53% gross margin Not bad, right? Everyone wins!

Not so fast! Are we the gas station, or are we the fancy taco place?

While a 53% margin is good on some things, it’s not great on anything we’re pricing a full $1-2 below what someone is willing to pay for something given the context. If we can sell a bottle of Topo Chico for 4 or even 5 dollars, why would we sell it for 3 dollars?

Over 5 years we’ve sold 1,211 bottles of Topo Chico, netting around $1,725. But if we would have priced the Topo Chico at $4 to start with, we would have netted closer to $3,040. This is how we’re starting to approach pricing this year, and we’re doing a lot better because of it.

Being a good person vs. charging more for something

If you're a kind-hearted person, you may find yourself resistant to the idea of increasing your prices when the cost of everything is already going up so much. If people can't afford groceries, why should I pile on by charging $1-2 more for a bottle of Topo Chico?

Answer: because you are not going to save the world by going out of business to give someone a good deal. You make a greater impact in your community from a place of financial strength, and in this down market, things are already precarious enough!

Don’t feel bad about charging more for things. You need that money, you deserve that money, and people are more than willing to pay you that money.

But I hear you. Another reason you don’t want to charge more for things is because you believe if you charge 4 dollars, not 3 dollars, for a bottle of Topo Chico, fewer people will buy the Topo Chico and your sales will suffer.

Mathematic magic

You know what? You are correct that fewer people might buy the Topo Chico with a $4 price tag. But will that actually hurt your sales?

We asked this at Fernseed when we considered raising the price on a $5 mini bouquet magnet to 8 dollars. My team was convinced the price increase would decrease the number of units sold.

“I don’t think it will!” I argued, only half convinced that was true. Sales probably would drop a little, but would our overall revenue decrease because of it?

But then I realized I was working on a 9th grade story problem.

Juan sells men's ties for $25 each at a small kiosk at the local mall. Juan's rent is $1,500 per week, and he needs to make double that to pay himself and the rest of his expenses. His sales last week were $2,800 (112 ties). Juan believes he can make his rent if he increases the prices of his men's ties to $39 from $25. But his employee thinks this is a bad idea. People like the $25 price point, and that is why so many ties sell!

Juan anticipates that he may lose 30% of his unit sales if he increases the price of his men's ties from $25 to $39. If he loses those sales, can he still afford his rent, plus the additional $1,500 in order to pay himself and the rest of his expenses?

Unit sales = 112 x 0.70 = 78.4

A 30% decrease in unit sales means Juan only sells 78 ties next month at $39 each. He loses 34 sales!

However, 78 x $39 = $3,042

While he loses 34 unit sales, he grosses $242 more, for a total of $3,042, enough to pay his rent of $1,500 with $1,542 left over for his additional expenses and to pay himself.

Wild, isn’t it?

When he increases the price of his ties by $14 per unit, even though unit sales drop considerably, Juan makes more money.

Is there anything Juan could add to ensure his ties fetch $39? What tiny expense could Juan add to the ties to increase the customer’s perceived value?

Maybe a box with tissue paper? A paper sleeve wrapped around the folded ties? What if he changes the quality of the paper the price tags are printed on?

Or maybe he adds nothing, and the ties still sell for $39 each.

How to figure out the math for your own proposed price increases

Let’s examine how to figure out what tolerance your business has for a proposed price increase. Luckily, there’s an easy formula!

First, pick a time period. This could be 30 days or 6 months, you decide.

Next, figure out what your unit sales were for the item you want to increase the price of, and what your gross sales were. For example, in 90 days, we sold 60 mini bouquet magnets at $5 each, for gross sales of $300.

Now, take your gross sales amount and divide it by your proposed new unit price.

[gross sales amount] ÷ [proposed new unit price] = [unit sales needed for same revenue]

For Fernseed, that looked like this.

$300 ÷ $8 = 37.5 unit sales

This means we need to sell 38 mini bouquet magnets (in 90 days/same time period) at $8 to equal the revenue we were making selling 60 at $5 each.

That’s a 37% decrease in unit sales for the same gross revenue!

Do we really think we’ll see a 37% drop off in sales based on a price increase of $3? Probably not. And now, we’re testing it.

In my next installment in this series about price increases, I’ll show you how raising prices on some of Fernseed’s best selling products has impacted our bottom line, increased team productivity, and even created opportunities for new revenue streams.

Meanwhile, please let me know if you’ve run the numbers on any of your best selling products or increased prices.