I was a Bench customer. I'm not surprised they shut down abruptly.

The difference between regular businesses and the startups trying to sell us all software.

Bench, the cloud-based accounting software company that ran TV ads during football games and positioned itself as a small business-friendly alternative to QuickBooks Online, shut down Friday with zero notice to its thousands of small business customers.

I mean, it shut down. It didn’t announce that it was shutting down by a certain date, or that it was being acquired and migrating everyone’s data to a new platform. It went offline completely. From one moment to the next, Bench was gone.

Some business journals report that Bench posted a notice on their website about the closure, but when I try to access their login page all I see is this:

If you were a Bench customer and you hadn’t recently backed up your bookkeeping data, that data might now be gone for good. Or, it might reappear on December 30 so you can export it and find a new bookkeeping service, depending on which version of the Bench website is up at the moment. No one at the company is answering requests for comment and apparently everyone who worked there last week was laid off.

This is not typical of startup closures, which, to be clear, do happen. The risk any of us take trusting any outside company with critical components of our workflow is that they might have a data breach or an outage. But it is notably weird for a company to shutter as swiftly and totally as Bench did with no explanation. It is incredibly disruptive to small businesses, especially at tax time.

Your accounting software, and your relationship with your bookkeeper, are the most important tools you have in determining the health of your business. Maintaining and reflecting on accurate books allows you sit at the steering wheel of cash flow and profitability so you can make decisions based on data. It is criminal that Bench took that data offline without warning. Bench had access to so many resources, and they chose to use none of them to do the simple thing of making sure their business customers still had access to critical data we need to make decisions like:

Do I need to reduce payroll?

Do I have enough profit left over to pay myself something this year?

Should I pay off the remaining balance on my credit card or hold it for overdue invoices?

I was a Bench customer! Like many Bench customers right now, I would have been devastated by this irresponsible action had I not been reading the tea leaves and migrated off the platform a month ago. Looks like I got out just in time.

As a Bench customer for 4 years, I had a front row seat when things went from functional, to bad, to the point of no return. I wanted to write about the Bench closure today because it’s a perfect illustration of platform decay, the steady decline where short-sighted, profit-driven choices erode software user experience, also known as “enshittification.”

Enshittification isn’t just an essay topic for the New Yorker, it has real world implications for everyone, and not just small businesses. It is the byproduct of a system that is structured to reward investors rather than serve customers. Businesses that don’t have investors rarely ever experience platform decay, which is why small businesses in your community tend to provide far better customer experiences than chains, while at the same time are dramatically under resourced.

The closure of Bench isn’t just a story about a software startup disappearing in the middle of the night and locking out its business customers. It’s an illustration of why it’s always more risky to partner with a large company than a small, local one.

It starts with the primary reason Bench, and startups like it, are uniquely vulnerable to platform decay while local businesses are not.

Why startups are uniquely vulnerable to platform decay

Let’s be clear about something: startups aren’t regular businesses.

A regular business is a business that has to make money to keep operating. Most businesses, including mine, are regular businesses. The only money that goes into a regular business is the money that business generates when people pay for the thing it sells. If the business wastes money on dumb ideas or pays people to do things that don’t matter for too long, it will eventually stop operating because the money will run out. Regular businesses still require startup capital, so they might take an initial infusion from outside investment, but the goal is to repay that investment through continued business operations. The people who invest in regular businesses aren’t Investors with a capital I, either. They’re usually the business owners themselves, family, friends, or (less commonly these days) a community lending institution.

Regular businesses can also sustain periods of loss, but that loss is typically financed by the business owner, who is forced to find new ways to satisfy customers to return to profitability and therefore stays in close relationship with their customer to mitigate risk by understanding and meeting their needs. It’s a symbiotic relationship, not always fair, but the risk stays with the business owner and initial investors, which is where it belongs.

Startups are not businesses. They mask as businesses because they have offices, employ people, and sell a product or service. But the difference between a startup and a regular business is that startups don’t have to make more money than they spend to keep operating. Investors (with a capital I) pump money into startups because they are gambling on a potential payout when one of the many startups they invest in is acquired or goes public. Profitability is not the goal of a startup; liquidity is. When liquidity is the end you begin with in mind, you’re not focused on building a great product your customers will love, you’re focused on maximizing investor ROI. This allows startups to make really bad decisions most of the time without facing financial consequences. Often, customers of startups can’t take their business elsewhere because startups have acquired their competitors until there is no elsewhere. Or they are holding information, like your customer data or 4 years of your bookkeeping records, hostage behind a code base that won’t export. The risk in the startup world isn’t with founders, who get fired from their CEO jobs and go on to start other companies, or investors, who can meditate and juice cleanse away the sting of a billion dollar loss, but with the customers—and, I would argue, employees of startups—who are left holding the bag because they were stupid enough to believe this company would provide for them, or solve their problem.

While many of us associate startups with software, I should be clear that software companies can be regular businesses! Building and selling software does not require endless capital. Just ask Jason Fried. He runs his software companies as regular businesses that make more money than they spend in order to continue operating. Regular businesses exist in every industry. Startups are concentrated in software, but exist anywhere businesses are considered “infinitely scalable.”

My experience with Bench

Bench was a startup, not a regular business. Their last round of investment capital—$60 million—came in 2021, just as their software product started getting shittier. I witnessed their television ads, which I’m pretty sure ran during the Super Bowl, while my experience as a customer was worsening. It often took months for my books to be completed even after I had uploaded all the necessary bank statements and payroll reports.

I started using Bench in 2020, in the height of the COVID pandemic, because my regular bookkeeper, who also did my accounting, retired early due to a sudden illness. Without bookkeeping or a good handle on how to use QuickBooks Online myself, I had no idea if my business was making money or bleeding money (in hindsight I can tell you it was both). I couldn’t find a local bookkeeper who was taking on new clients because in 2020 everyone was slammed dealing with the PPP and EIDL loans and everything else. In between monitoring my oldest kid as he navigated online kindergarten, I Googled an alternative to QuickBooks Online and found Bench.

Bench had great UX. They had great onboarding. The copy on their landing pages addressed all my pain points. I could pay Bench a couple thousand dollars (chump change once my EIDL loan hit my bank account) to migrate my data from QuickBooks into their software, and they promised me that, even though their app was a walled garden (meaning: doesn’t play nice with other accounting softwares and isn’t easily exportable), I would always have access to my data and could export it at any time. With that potential dealbreaker addressed, I signed up.

I loved Bench at first! Compared to QuickBooks online, it was easy to navigate if you were a business owner and not an accountant. The dashboard provided me with an at-a-glance snapshot of how my business was doing. Accountants didn’t love Bench, but they could work with it, and understood why as a business owner I would opt for a reporting tool that was easier for me to read even if it displayed months in backwards order on a profit and loss statement.

I also loved Bench because I not only had access to their software, I had a one-on-one relationship with a dedicated remote bookkeeper via their in-app chat tool. If things got complicated, I could book a call with my bookkeeper, and I did that often.

In the beginning, Bench struck me as the perfect combination of software and service. It was the product I believe the founders set out to build, and it worked well for me. I believed in it so much, I recommended it to other business owners. But the problem with startups is that, in the end, they will always do what startups do. They cannot stay in equilibrium because they have to grow. In order to grow, the Bench board fired the founder from his CEO position in 2021, and by 2022, platform decay was well underway.

By Q4 of 2024, Bench was in its death throes, and here’s how I knew.

Bench tried to replace real bookkeepers with A.I. and it wasn’t going well.

When I first joined Bench in 2020, my bookkeeper was a guy named Colin. Colin lived in Portland, Oregon. Any time I wanted to chat with Colin about my books, I used his Calendly link. Once we talked for 45 minutes about how my cost of goods was being calculated, but also about his recent trip to Seattle. I could be real with Colin about how things were going in my business. I think I even cried on the phone with him once.

I was always shocked when Colin was still with Bench month after month. It felt too good to be true. I’m paying half of what I would for a local bookkeeper, but I’m still feeling all the benefits, maybe even getting more value, and you’re telling me Bench isn’t planning to outsource Colin?

Then one day in 2022, I got the email I’d been dreading. Colin was leaving Bench, and I’d be working with a new bookkeeper, Bharani. Bharani had fewer Calendly slots available for calls, which made me think we were dealing with a big time difference. That didn’t bother me as much as the fact that my books never seemed to be finished. In April of 2024 I was still waiting for my January, 2024 books to be completed. If Colin got behind on books I’d get a real-world answer, but if Bharani was behind, I got a canned response, something like: “Rest assured, your team will promptly contact you if further clarification is necessary. As of today, January's categorization comments have been addressed, and your adjustments are undergoing thorough review by the Bench Team.”

Meanwhile the in-app bookkeeper chat tool was slowly being replaced by A.I., so I wasn’t chatting directly with Colin or Bharani about how to categorize my transactions, now a bot was lecturing me on the difference between business and personal use of office supplies.

I don’t think most customers are asking their favorite software for more in-app A.I. tools, it’s typically the investors or board at a startup pushing A.I. for A.I.’s sake, because startups that utilize A.I. can attract even more of that sweet, sweet investor money, which gets them closer to liquidity. The fact that Bench got $60 million in funding, Colin left, and now we have A.I. replacing human bookkeepers? These were my first clues that things were going down hill. How is it that my customer experience is getting worse, but you’re running ads during the Super Bowl? Sounds like textbook enshittification to me!

Bench was months behind on completing my books, and kept blaming me for it.

Bench made a big deal about upgrading their bookkeeping status toolbar in 2023. With this new interface, we were supposed to easily be able to see if Bench was waiting on us for documents, or we were waiting on Bench to complete something.

When you don’t have your books wrapped, you don’t know if you made or lost money the month before. You don’t know the impact of your decisions, and it’s exhausting. For example, midway through 2024 one of my employees resigned and I decided not to re-hire her position. I thought saving on payroll would increase profitability, which would allow us to repay some debt faster and save on interest, even as our sales declined seasonally. But month after month, Bench never wrapped my books, so I couldn’t easily verify my theory. I couldn’t weigh the benefit of working more hours than I wanted to on the retail floor while saving on payroll, so I kept working to the point of burnout.

Even more critical is the need to present lending institutions with up-to-date financials if you want to apply for grants, loans, or other programs. I was applying for an SBA loan for commercial property in 2024 but I did not have completed books from Bench. It is really, really bad when you’re applying for a loan in Q4 and you realize the income statement you just uploaded did not have accurate line items for payroll wage and taxes for the entirety of Q3. I started keeping tabs on documents I had uploaded to Bench to prove that I had, in fact, uploaded them, and Bench continued to request that I upload these same documents so they could complete my books.

I got denied for that commercial real estate loan, by the way.

They started double charging me for bookkeeping by accident, then gave me a massive refund.

I started doing line-by-line analyses of my profit and loss statements to check for Bench errors, and I noticed that for four straight months, Bench had been charging me $719 for bookkeeping instead of the regular $365. I couldn’t find anything about a price increase when I searched back through my email, so I contacted their billing department. They confirmed, almost to my surprise, that it was a mistake, and they refunded me nearly $2k in erroneous charges.

By this point I had already met my new, local bookkeeper at a good ol’ fashioned Chamber of Commerce networking event and had begun the process of working with her to migrate my data off of Bench and into Xero. I officially cancelled my account with Bench as of December 1st, and I couldn’t be happier.

But I know from working in software startups that a billing mistake of that magnitude likely isn’t contained to a single account. If Bench really had 35,000 customers and even 10% of them were overcharged like I was, a $1,500 refund would cost… $5.2 million? This is the problem of building things that scale while no one is paying attention. Is that looming potential refund a reason Bench went out for a pack of smokes and never came back?

So what’s next for Bench customers?

According to the Bench landing page (when it’s up), customers will be able to export their data as of December 30, 2024. Bench is recommending their customers check out an extremely early-stage startup called Kick for bookkeeping, probably because Bench investors have a stake in Kick, too. I would steer clear of Kick if you’re in the market for bookkeeping, and instead work with a local bookkeeper who uses their favorite industry-standard accounting software, such as QuickBooks, Wave, or Xero. That’s what I did. If I would have been able to connect with a local bookkeeper in 2020, I would never have started using Bench, but I’ve learned the hard way to never choose a startup software over a local business, even if in the beginning it’s more convenient.

Divesting in startups and public companies that treat their customers like garbage

It is not easy, as a small business owner with very little power or influence, to stop working with companies that regard you as a product, not a customer. I wrote about this two years ago when I analyzed our relationship to Shopify. You’re a “product” because, even though you are paying for the service, in the larger view of the company, you’re just part of a user base they use to pitch investors. Growth is the goal, not refinement, not accuracy. So your customer experience will always worsen until it’s so bad you have to move on. The companies don’t care about your experience because they don’t have to, unless it’s affecting their net promoter score in advance of a funding round, which is only calculated in the aggregate. They’re not motivated to fix a problem for you, because your individual experience doesn’t matter to them financially.

When you hire a local company, your individual experience does matter. It’s still financially motivated, sure, but that doesn’t make it any less impactful.

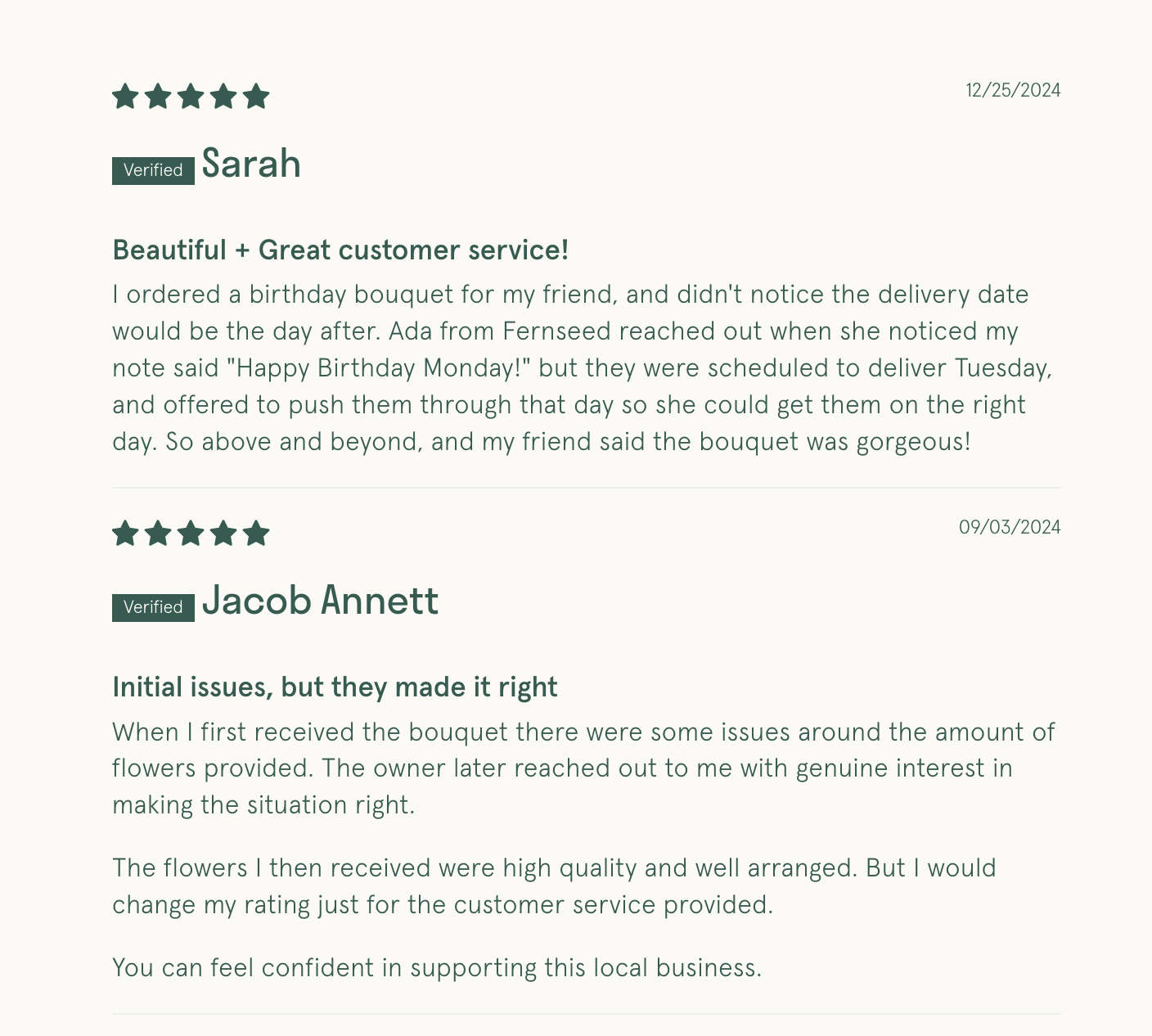

We live in a society where we expect enshittification, so when it doesn’t happen, we’re pleasantly surprised. I sometimes feel like we have a super power at Fernseed to warm people’s hearts with service that goes above and beyond.

But we’re a flower shop! We’re an easy local option. Where is that option in marketing, insurance, software, and sourcing? Does it exist?

I am willing to pay more for local services. I am willing to inconvenience myself. But in some industries, I’m not sure we have a choice in what kinds of companies we work with and therein lies the problem.

As an addendum to what I’m writing here, I’m including a list of companies Fernseed works with that make me uneasy, but where I’m unsure how to divest, or it’s complicated.

I hope in the coming year to discover ways of further detaching from companies that make us feel gross inside, and to support companies that are committed to limiting growth and focusing instead on relationships, trust, and community.

I welcome your thoughts and advice in the comments! Where have you successfully divested? Where are you stuck? Did Bench rip you off, too?

Some companies I work with at Fernseed and where I’m at with that.

Payroll services

Gusto: Great in the beginning, by the end cost me hundreds of dollars in fees from the Washington Department of Employment Security for paperwork not filed on time, company never responded. Penalized me for not having enough money in the payroll account by requiring I run payroll 4 business days before it was due, which was impossible because I had to run payroll before the pay period ended. I switched to Homebase.

Homebase: Seems fine so far, but I don’t have any faith that will continue. During onboarding told me their payroll support customer service is U.S.-based but as far as I can tell it’s outsourced to an overseas call center.

I could switch to a local company for payroll, but Homebase is also our scheduling tool, and that works well. It’s not terrible at the moment, so I’m sticking with it, but I don’t love it.

Marketing

Google: I don’t pay for ads, but I do maintain our business profile. Despite working in digital marketing for years, I can’t figure out their Adwords interface. If we were a bigger company, I might pay someone to manage search ads for us, but we just don’t have the volume at the moment. We used to pay for ads and it didn’t make a difference when we pulled them.

Yelp: Their “ad managers” are early career salespeople who use prospecting techniques popularized by Bitcoin scammers and they are incredibly rude to businesses who politely ask them to never call again. Most small businesses get a call from Yelp once a week. I will never advertise with them, but I have to have a business profile on their website—literally, I cannot remove it as it doesn’t belong to me.

Meta: I’ve thought about leaving Instagram entirely… and I’m still thinking about it. We automate posting from Instagram to Facebook because I just don’t care anymore. Neither platform is how I want to communicate with my customers.

Klaviyo: Email marketing software I use because the flows and automations work well for us, but I’m probably paying for more than I’m using. I do like email marketing, however, as I can control my list and who receives email. I’m pretty indifferent to Klaviyo. They’re a public company as of 2023, so I’m sure now it’ll be all about maximizing shareholder value. I have noticed their customer service rely more on automation since then now that I think of it…

Vistaprint: Stopped printing most of our materials with Vista or any of the other print companies and instead print on our own materials at the shop on an ink jet or with Paper Press Punch, a Risograph studio in Seattle where I’ve recently started learning how to print.

I am a fan of direct mail and email marketing, where we actually own customer contact information and choose how to use it, versus being subject to an algorithm. Direct mail is expensive, but I enjoy making print materials like zines and I think our customers would enjoy receiving them. It feels way less gimmicky to me. SMS marketing is also an option, but you need a service like Klaviyo to manage it.

E-commerce platform

Shopify: Divesting from Shopify would be incredibly complicated at this point, but if we were ever planning to grow I might look into switching to Woo Commerce. Shopify outages are disruptive to our business but are infrequent. I have no love for this company or its founders.

Supplies

Amazon: This year I’d like to stop buying any supplies, even the hard to find ones, from Amazon. Operationally it’s much easier for us to order supplies online versus a manager driving to a store to purchase them, which becomes an insurance issue on top of everything else. All we need to do here is make a list of everything we buy from them and find an alternative source, then make a spreadsheet with all the sourcing info.

Temu: Before there was Temu, there was Alibaba, and I used to buy in bulk on Alibaba for things like plastic watering cans you couldn’t get in the U.S. at a price that competed with chain garden stores. Now that there’s Temu, I can buy those same things in quantities of 10, not 1,000, but so can everyone else. It’s a race to the bottom, everyone loses, so I guess I’ll go back to selling $40 watering cans that no one ever buys but are at least ethical. We do buy packs of die cut 50 stickers on Temu and sell them at the cash register and I make about $1,500 per year on those. Am I proud of that? No. Am I trying to stay in business? In the least harmful way possible.

Uline: After #stickergate happened earlier this year, I thought: but we’re all still using Uline? Their customer service is top-notch and their products are quality and reasonably priced and I hate them for it. I really need to get off their teat this year.

Insurance

Farmer’s Insurance: When a car crashed into our business, the adjuster working on our claim made mistakes on calculating loss of business revenue and I was the only one who caught it. I’ve since switched agents, but I have no love for anything insurance related.

I left Bench and went back to Freshbooks a couple of years ago and thought I was the problem because they never could finish my books and kept asking me for things! Now I’ve left freshbooks for QBO and am doing my own books. Freshbooks went from a local company (they started here in Toronto) to a completely enshittified mess that is charging more in two months than I paid for a year previously and keeps cutting services. They recently cut their premium level services such as a distinct helpline and dedicated account managers with all levels of accounts have to use the AI chatbot. Also, after switching from Stripe to their payment processor, WePay, they shuttered that after a couple of years and everyone was told to go back to Stripe, but you couldn’t connect to your existing Stripe account, you were required to apply for a second Stripe account specifically via Freshbooks. Likely a kickback involved, I guess. I didn’t want a second Stripe account as I’ve already run over 1.5million through my existing account and gave built up good standing. FreshBooks said, “oh well. been nice knowing ya”. I was with them from their beginning and they didn’t give a damn. Oh well.

Katherine, I though of you as I just got an email pitch from the zombie corpse of Bench recasting Bench as a outsourced bookkeeping for Accounting practices...omg.

(which for me is doubly laughable because CPA's are the worst people to do or manage bookkeeping for businesses to begin with!)