That time I got audited by the state department of revenue

What I learned, what I would do differently, and how it turned out that the stated owed us a refund

Plus: read through to the end of this because I have a tidbit at the end that is 🤯, and if you run a small business that collects sales tax, I would love your input.

Last year, the week after a car crashed into the front of our business, I got a letter from the Washington State Department of Revenue informing me that the Fernseed had been selected for a random excise tax audit.

I had to blink a few times at this letter.

This is it, right? The thing of where we’re… getting audited? We’re being audited. Right?

It’s a moment I’m sure all business owners dread to some degree. Either you know you’re about to entire into a bureaucratic nightmare pulling a bunch of old records, or you’re just plain terrified of what this all means.

Because this is a universal experience—either it’s already happened to you or it will—I wanted to talk about my experience getting audited. In particular:

Why I wasn’t intimidated by the audit process

One big mistake I think I made during my audit (and how I would do things differently next time)

Why I didn’t hire my accountant to represent me during the audit process

One thing I discovered during my audit that I believe is shockingly unfair and that I want to work to change within the state of Washington (the 🤯)

How I ended up concluding my audit with a refund check from the state for $819.17 rather than owing the state money

Let’s start with why I wasn’t intimidated by the audit process.

Don’t fear the auditor

You don’t have to be that organized

I knew it was not a matter of if Fernseed would get audited by the state, it was when. (I actually found it kind of funny that the other thing I “knew” would happen in the business was a car crashing through the front of the shop, and these two things happened in the same week.) I knew this because my business friends at Gardensphere, a garden center a few blocks from the original Fernseed location, chuckled at me some years ago when I casually dropped, “I hope I never get audited,” into a conversation. Their response—Oh, you will, everyone does!—normalized it for me. They even went so far as to give me this helpful tidbit: You don’t even have to keep organized records! If you hand them a shoebox of receipts, it’s their job to sort through to find what they’re looking for.

Thanks, Gardensphere! 🙌

Prepare by educating yourself a little

Another reason I wasn’t intimidated: Years ago when setting up my business, I went to one of those department of revenue workshops for new business owners. If your state offers workshops, I highly recommend attending one, even if you’ve been in business a while. The workshops cover the basics on collecting and remitting sales tax, and all the other little ways the state taxes business activity you might not be aware of (but still owe taxes on). It was at this workshop that I learned about Tax Paid at Source, and Use Tax, which I’ll talk about in more detail when I explain how I got a refund.

Washington also offers tax consultations for businesses, which I imagine is sort of like an audit except the business owner is driving the bus. Believe me, I know it’s scary to not know if you’ve been doing something wrong for years, especially if that error could result in you owing the state thousands of dollars, but I would encourage you to at the very least write down the questions you have about how you’re supposed to collect or report taxes, highlight those gray areas you want answers on, and set aside some time (I know, hah) in the next year to get those questions answered either by your accountant or by the state. It was nice to go into the audit process knowing I had conducted business by the book (i.e. tax code) since we opened in 2019. Give yourself the gift of that confidence by seeking it out preemptively!

The “revolt” part

The final reason I wasn’t intimidated by the audit process—and this leads to my biggest mistake during the audit—is that I believe in the value independent storefront businesses like ours provide regional governments in the form of tax revenue and overall economic health. However, as I’ve written before, we’re not exactly fairly compensated for that value, especially given the risk we take on.

I wasn’t intimidated because I was enraged, really. Enraged that after starting a business that generated over $280,000 in tax revenue for the state since its inception, and leading that business through the worst health crises in recent U.S. history, then through one of the toughest economic landscapes that followed, my “thank you” was to have a department of revenue employee comb through three years of my documents—years that included 2020, mind you!—to ensure every last tax dollar potentially owed to the state was, indeed, paid to the state.

With this indignation festering, I basically turned into Jack Nicholson at the end of A Few Good Men on my auditor.

I have neither the time nor the inclination to explain myself to someone who rises and sleeps under the blanket of the very [TAX REVENUE] that I provide and then questions the manner in which I provide it. I would rather that you just said "thank you" and went on your way. Either way, I don't give a damn what you think you're entitled to!

So, friends, that was my mistake. I went a little off the rails on my auditor, like I was Jack Nicholson, and they were Tom Cruise trying to question me.

Things that actually came out of my mouth during some of our phone conversations include:

“I’m a tax paying citizen of this state, so technically your boss works for me.”

“If it turns out we do owe the state money, then you can get in the back of the long line of people this business owes money to, including myself.”

“I am not going to accept the casual suggestion that I work the weekend—a sacred time I set aside for family—to produce documents just so you can hit some arbitrary deadline.”

While the spirit of these phrases was right, the delivery was misguided. I was a hostile auditee. I went through the process with conduct unbecoming a member of the small business community. I let the messy insides bleed out a little when it was not beneficial to do so. What can I say? It’s been a hard few years.

Why not hire an accountant?

Because the whole situation got me fired up to a degree that might not have been warranted, you might think I should have hired my accountant to represent me through this process, at least to create a buffer between me and my bureaucratic triggers, right? But I would have had to pay an hourly fee for her services, and I could not justify spending another $1,500-3,000 on accounting for compliance when I already pay her firm (~$150) to file my sales tax returns every month. To be clear, this isn’t a dig on my accountant! She should be paid for her services. This is another reason I was annoyed by the state’s assumption that a small business owner has the resources for an audit. I didn’t have the extra money to spend on this… but I didn’t have the time, either. In the end, I chose to spend *time* I didn’t have versus *money* I didn’t have on the audit, and this is where my pushback began.

Take a look at this list of documents requested in the initial audit letter.

Records Requested

We will initially review the following records for the audit period:

• Supporting documents used to file Excise Tax Returns

• Federal Income Tax Returns

• Chart of Accounts

• Summary accounting records, such as check registers, general ledgers, sales journals, Profit & Loss statements and Balance Sheets

• Bank Statements

• Sales Detail Report

• Sales Invoices

• Expense Detail Report

• Purchase Invoices or Paid Bills

• Depreciation Schedules and supporting asset invoices

• Reseller Permits for wholesale sales

• Supporting documents for all deductions and exemptions claimed

• Sales by State Apportionment Reports

• Payroll by State Apportionment Reports

• Property by State Apportionment Reports

• Retail Sales Tax Reported on Individual Streamlined Sales Tax Simplified Electronic Return (ISR)

• Working Papers/Supporting DocumentationWe may request additional documents as the audit progresses.

Are you laughing at this the way that I was laughing at it? In my first couple of emails with my auditor I asked what I would actually need to prepare and send them. ALL OF THIS? For a period of three years?

Her response was to suggest we start with the first 5 on the list.

While it’s easy for me to pull our federal income tax returns, I was a confused by vague requests such as “chart of accounts.” These requests for documentation are so vague they’re unhelpful bordering on overreaching.

I asked for clarification on a few of them, including the “supporting documents used to file excise returns,” which came down to providing documentation to back up the dollar amounts we calculated when we remitted our monthly sales tax to the state. Keep in mind you don’t provide this “proof” when you file, the state takes you at your word. But now during the audit, you do have to prove it.

A quick aside about collecting sales tax in different U.S. states

I’m about to get into a little e-commerce “how to charge sales tax” thing that might be a little overkill, but I think it’s important to get clarity on because I did not have the vocabulary for this until I went through my audit and now that I do, I realize why moving from Illinois to Washington made collecting and remitting sales tax so much harder. (I had a business in Illinois that was not Fernseed, but did collect and remit sales tax.)

Illinois is an origin-based state with regard to how taxes are charged, meaning that if you are selling within Illinois, you charge the sales tax rate based on where the items are being sold from. If you have one location, you have one simple tax rate within your state: yours.

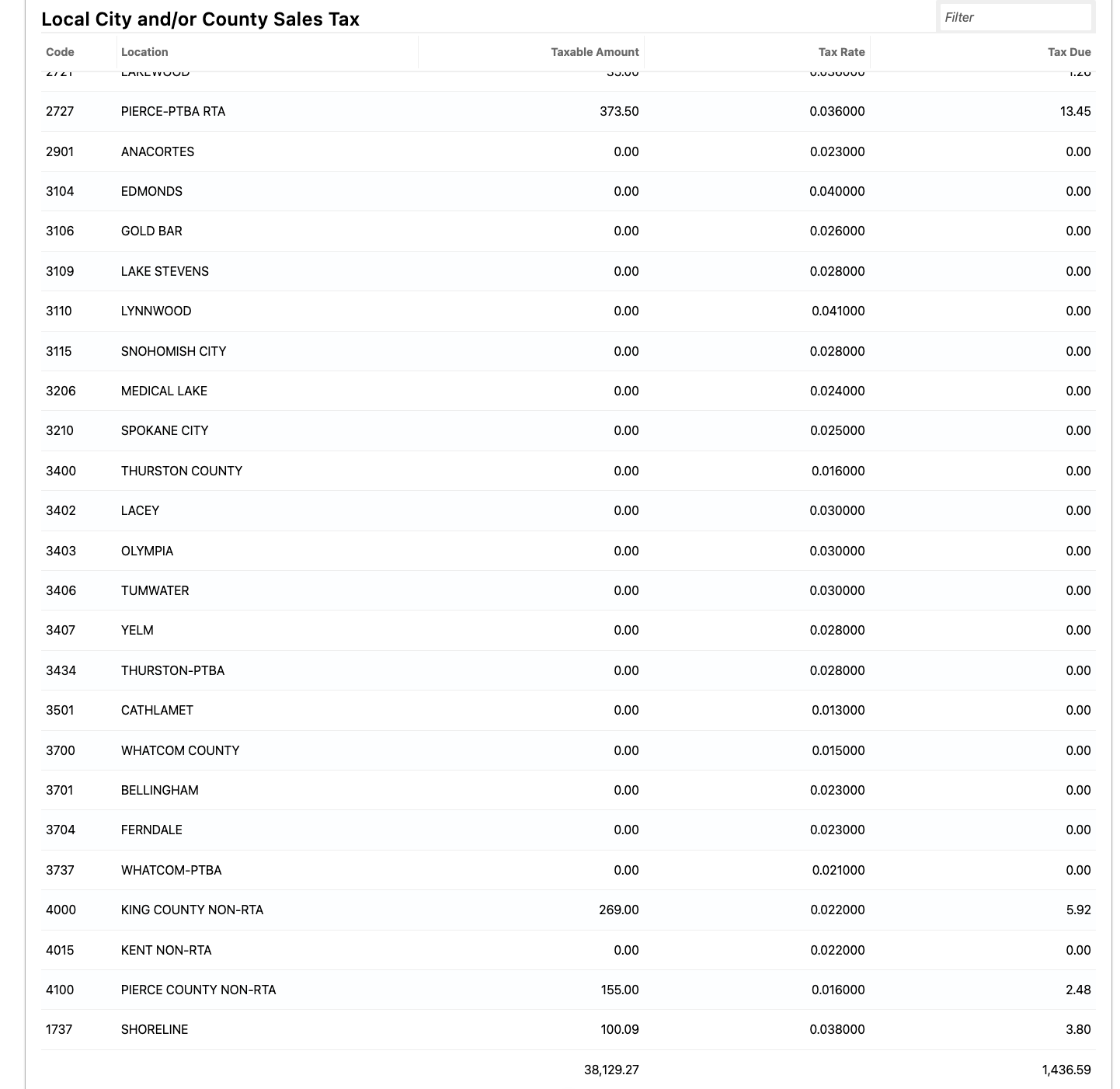

Washington is a destination-based state! That means that every time you sell something online to someone in Washington, if you have nexus in Washington (obviously we do), you must collect taxes based on the tax rate of the destination of the product, not where it originated. In other words: I charge the tax rate based on where the product is going, not where Fernseed is. Check a sample snapshot of one of our sales tax returns within this state! I have to hire an accountant to file these because they’re so specific, even if you enter the numbers exactly like Shopify reports them, sometimes they don’t “balance” on the state website side and you can’t submit them. (This has to do with how numbers ending in .66667 are rounded, I think.)

So not only are we a.) paying for software (+ sales tax on that software) to help us calculate the rates to begin with, we are b.) paying an accountant $150 each month (+ sales tax that service) to file our complicated tax returns in Washington. And now… you want me to spend several hours digging back through all the reports Shopify generated in order to file those complex returns for a period of three years to prove that the software and bookkeeping we already pay for was accurate?

Yep.

They’re asking for too much

But what really broke me was the bank statements. The list says, “Bank statements.” I asked, which ones? The response was: all of them for the period in question.

Now, you may recall that I use the Profit First method for accounting, which involves using multiple bank accounts to manage cash flow. I have also opened and closed checking accounts with banks that did not make this system of money management easy. So I have somewhere like… 12 total bank accounts that were used over the three-year period being audited (even though I only have 5 active bank accounts today). The state was asking me to furnish monthly statements for any accounts we had open for every month during the audit period, which equates to something like 200 total PDF bank statements that they wanted in a .zip file uploaded to their portal.

Perhaps the banks would simply .zip all historic statements on my behalf? You would think maybe, for all I have paid them in fees! But nope, no. It costs $1.50 per statement to have them .zip it for you. (The bank I’m now with full time just did it for me for free… even though they usually charge for the service. Community banking! 🙌 But that was only the 5 most current accounts for 9 months.)

I told the state that there was no quick way for me to do this. That while I used to save my statements in a .zip folder (like they told me to do at the beginning business owners tax workshop), I stopped doing that in July 2020 when everything got to be too much. I told my auditor that it would take me an entire day to get them this information based on the disparate locations of the accounts and the sheer volume. Her response was essentially, “When, then, will you have a full day to work on that for me?”

Would this be considered “lawyering up”?

My response to that was, unfortunately, “I guess I’m just curious why you can ask for all this stuff without a warrant, because we are a private company, and while I’m sure there’s some state law that gives the department of revenue permission to dig through the private bank records of individuals without reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing confirmed by a judge in a court of law, it now seems weird to me that that’s a thing, so I’d love to see the state legal code that outlines that before I cooperate further, thank you.”

I just… I have some real problems with authority. And I acknowledge the privilege it sometimes requires to not cooperate with government entities, but let me say that I’m always willing to use what privilege I have to push back on behalf of others who can’t. Because think about it for a second: why *should* the state be able to pull your private bank records without suspicion of wrongdoing? And maybe they can, but then show me where it says.

And you know what? My auditor DID show me where it says:

Every taxpayer liable for any tax collected by the department must keep and preserve, for a period of five years, suitable records as may be necessary to determine the amount of any tax for which the taxpayer may be liable. Such records must include copies of all of the taxpayer's federal income tax and state tax returns and reports. All of the taxpayer's books, records, and invoices must be open for examination at any time by the department of revenue.

Great, okay! We have to open our books to the department of revenue at any time, I get it. There is is codified into law or what have you.

Then I thought back to that shoebox of receipts Gardensphere mentioned to me years ago when discussing audits: it doesn’t have to be organized.

All of the taxpayer's books, records, and invoices must be open for examination at any time by the department of revenue.

My books are open! I’m not trying to limit the documents or records I’m sharing with the department of revenue. I don’t have anything to hide! What I don’t have is the time to organize this shoebox that they are in. Can I just… hand them the shoebox?

I asked if I could simply make my auditor a read-only administrator on our bank logins so she could pull those records herself. The answer from the department of revenue was that that would be a privacy concern, and the only way for them to access the records was if I got them out of the digital, password-protected space.

It was at this point that I had created enough friction that my auditor felt it necessary to jump on a call with me and her supervisor (the “boss that works for me,” remember).

(I told you, I’m not proud of all of this, I’m sorry!)

I told them that this process was overly burdensome on me as a sole business owner, and that my primary concern had to be keeping the business afloat during this excruciating economic downturn. I told them it felt like a slap in the face to ask me to spend a full week pulling documents that I was willing to give them access to but just didn’t have in the format they wanted, and that I wanted to know what my options were in terms of limiting scope.

I referenced a document they sent in their initial engagement with me that mentioned something called “sampling,” which sounded to me like they could take a smaller sampling of data from a more limited time period to ensure it matched the numbers reported, and that if those samples matched, they could assume the rest of the time period would, too.

Further, our gross receipts for the 3 years in question were around $1.1 million. That means over the three years in question, we collected and remitted around $113,000 in tax.

Now let’s say we assume that 3 percent of gross tax receipts had errors, and that ALL those errors resulted in Fernseed paying less to the state than it owed. The dollar amount owed would be $3,390.

Is it really worth anyone’s time, either on the business owner’s or the state’s side, to do a deep dive into the complete accuracy of these filings to find errors that total less than $3,500? And a 3 percent assumed error rate is pretty high!

I told them I didn’t like how the state approached the audit process assuming that we hadn’t kept good records, like we didn’t know what we were doing. I knew what I was doing, I just didn’t have time to continue to maintain backup paper documentation of everything during the pandemic and its aftermath.

Maybe the state owes me money

“Look,” I told them. “You’re not going to find any underpayment in this audit, I guarantee you. The only thing you’ll find is that—again because of pandemic lack of time and a long story about how my original bookkeeper retired early because of COVID and I couldn’t find a bookkeeper for a while who was taking on new clients because of the pandemic mayhem—I didn’t report Use Tax OR Tax Paid at Source receipts for half of 2020 and all of 2021 and 2022. But I figured it didn’t matter because the Tax Paid at Source was always going to be higher than the Use Tax, so we were actually overpaying versus underpaying.”

“Then it’s possible the state owes your business money,” they offered. (Honestly I feel like they were impressed that I used the words “use tax” and “tax paid at source,” and I have to once again stress: the free workshop.)

They told me that while they understood my frustration, some of what I was complaining about were things I would need to take up with my state representative, not my auditor at the department of revenue.

Fair enough!

“But I’m not willing to go through 40+ hours of pulling old bank records and uploading them to a portal to get that money back. It’s not worth it. So what can we reasonably do to limit the scope of this audit?”

They told me they would look into it.

The state legit backs off, I can’t believe it

A few weeks later my auditor got back to me to tell me that they were going to proceed with my audit without requiring the rest of the records that I had not yet submitted. They wanted the Use Tax reports and the Tax Paid at Source receipts, but the rest they would, in their words, “accept as submitted.” As in: they’ll accept the returns we filed each month already as being accurate without requiring me to prove that they were accurate by pulling 216 separate bank statement PDFs.

A couple months after my documents were accepted as submitted the state got back to me with their audit summary.

“A refund in the amount of $819.17 will be sent to you on Feburary 8, 2024. This refund includes interest in the amount of $26.35. This refund is for credit established during an audit.”

So yes, I got a refund. And no, I’m not proud about the way in which I pushed back so strongly on what they were asking me to furnish during the audit. But I am proud of the fact that I did question the scope, which apparently can be limited if you request it to be, at least within Washington, because now I can encourage other people to push back—politely!—on what’s being asked of them if it feels like too much.

It’s not a crime to have an unorganized shoebox.

The thing that still bugs me about sales tax

That, however, is not the key thing I discovered during my audit. It was something else that should be glaringly obvious, but somehow never occurred to me or any other business owner whose attention I brought it to.

I already believe that it is pretty unfair that small business owners are not compensated for being the key operator in a tax collection system that, really, has nothing to do with us. We’re not the ones being taxed when someone makes a purchase, the customer is. We are charging tax on behalf of the state, collecting it, holding it for the state, then paying an accountant to calculate the amount we need to send back to the state, and sometimes having to spend more time and money so the state can ensure we calculated it right. Big companies have the staff to do that, but do I, as a tiny business owner? But hey, it is what it is, right?

Except wait.

Each time a customer pays for something at Fernseed with a credit card, I pay a payment processing fee. I pay that fee on the entire amount collected, not just the amount the customer owes me, and that amount includes tax.

When a customer made the above purchase and paid with a credit card, I not only paid payment processing fees on the $80 we collected on our products, but I paid fees on the $8.25 in tax I collected on behalf of the city and state. My average credit card processing fee rate is 2.9%, which amounts to $0.24 on the tax collected on this transaction. So while I collected $8.25 in tax, I have only pocketed $8.01 after the credit cards took their cut.

However the state requires me to pay back the amount collected before processing fees. I can’t collect $8.25 in tax, then remit $8.01. I would get audited! I have to remit the entire amount collected. I am out the $0.24 on this transaction.

Earlier I said that at the time we received the audit letter, by my calculations, Fernseed had collected around $280,000 in sales tax for the state since its inception. If you calculate that 90% of those sales were credit card, that’s $252,000 in sales tax processed on a credit card with a 2.9% average processing fee paid to the credit card companies that I never see back. The total amount that’s evaporated in this business because of this gap: ~$7,500.

The funny thing is, when I mentioned this to other business owners some of their first reactions were, “Well, that’s deductible. Credit card fees are a deductible expense!”

Yeah, they’re deductible, meaning I don’t have to pay tax on profits because of the expense that offsets the amount of profit I make. But it’s still a real expense! I would have had $7,500 more dollars in cash in my business to invest in new equipment, pay employees, pay myself, etc. had I not had to do the job for the state of collecting sales tax and then pay to do it.

Because of the ease of credit cards, I am willing to pay the thousands of dollars in fees I pay each year on payment processing of the products we sell and the money we realize based on those sales. What I find unconscionable is that the state believes they don’t need to pay their share of fees to the credit card companies, based on money they require small businesses to collect, when those businesses have no other reasonable way to collect that tax other than paying a company that charges fees to collect it.

I checked with the state of Washington, and their response is: we know about this, and we don’t care.

What I am now trying to figure out is whether other states have a program to help share the cost of the credit card processing fees. I don’t have an answer to that yet! I tried working on it this week but not kidding another car crashed into my store. It never ends!

Meanwhile I would love to hear about your experience in your state (assuming you’re based on the U.S.), and whether or not you’ve ever noticed this reverse loophole with the tax collection and the credit card fees?

Thank you for writing! Similarly, with personal income taxes, you’re wayyyyyy more likely to be audited if you make under 25k a year. I got audited one year as a student when I made 15k. It was so pointless - and turns out the feds owed me money too!

I read this article in the Times last year about how the earned income tax credit triggers audits, which, of course, means lower-income households. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/18/us/politics/irs-audits-black-taxpayers.html It shocks me that there isn’t more transparency and oversight about who is getting audited (both in business and personal) and what the results of those audits are based on income levels and other demographics. Auditors have too much power, it’s such an intimidating process.